In 1969, an artist named John Dowd lived in Park Slope. He was a pop art painter, a bartender at a gay bar and a pioneering creator of a medium in flux: the zine.

Dowd’s zines — self-published booklets often produced via copy machine — made him a staple of the early 1970s’ correspondence art movement. The late artist helped spawn a new method of networking for countercultural art, but his work has been sparsely exhibited… Until now.

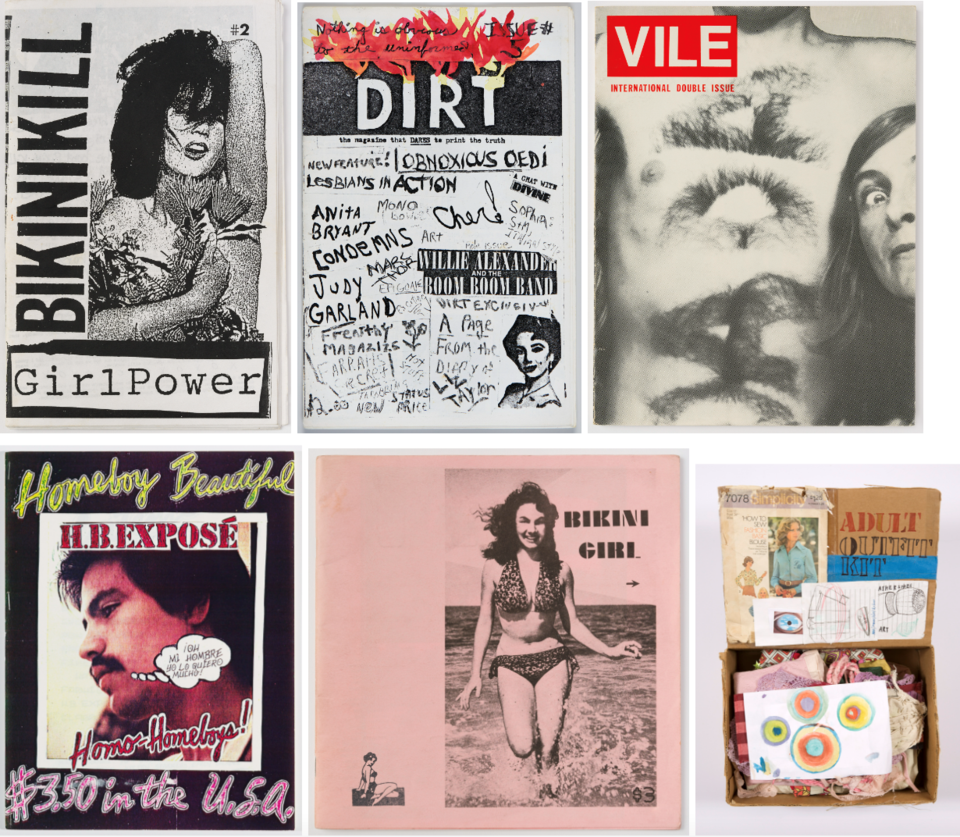

This fall, Dowd’s zines will open a new show coming to the Brooklyn Museum, “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines,” accompanied by the work of countless other unconventional artists.

Debuting Nov. 17, the exhibit will remain on view until March 31, 2024. Branden W. Joseph, Columbia University’s Frank Gallipoli professor of modern and contemporary art, and Drew Sawyer, previously the Brooklyn Museum’s Philip and Edith Leonian curator of photography and now a curator at the Whitney, have been developing the show since 2019.

“The exhibition is an attempt — and seems to be the first attempt in a large-scale museum setting — to look at zines by artists as a distinct medium, with a history and relationship to other aspects of the artist's work,” said Joseph.

The exhibit traces zines from 1969 to the present, encompassing more than 800 works: Actual zines, along with related paintings, drawings, photography and film. The curators separated the material into six roughly chronological parts.

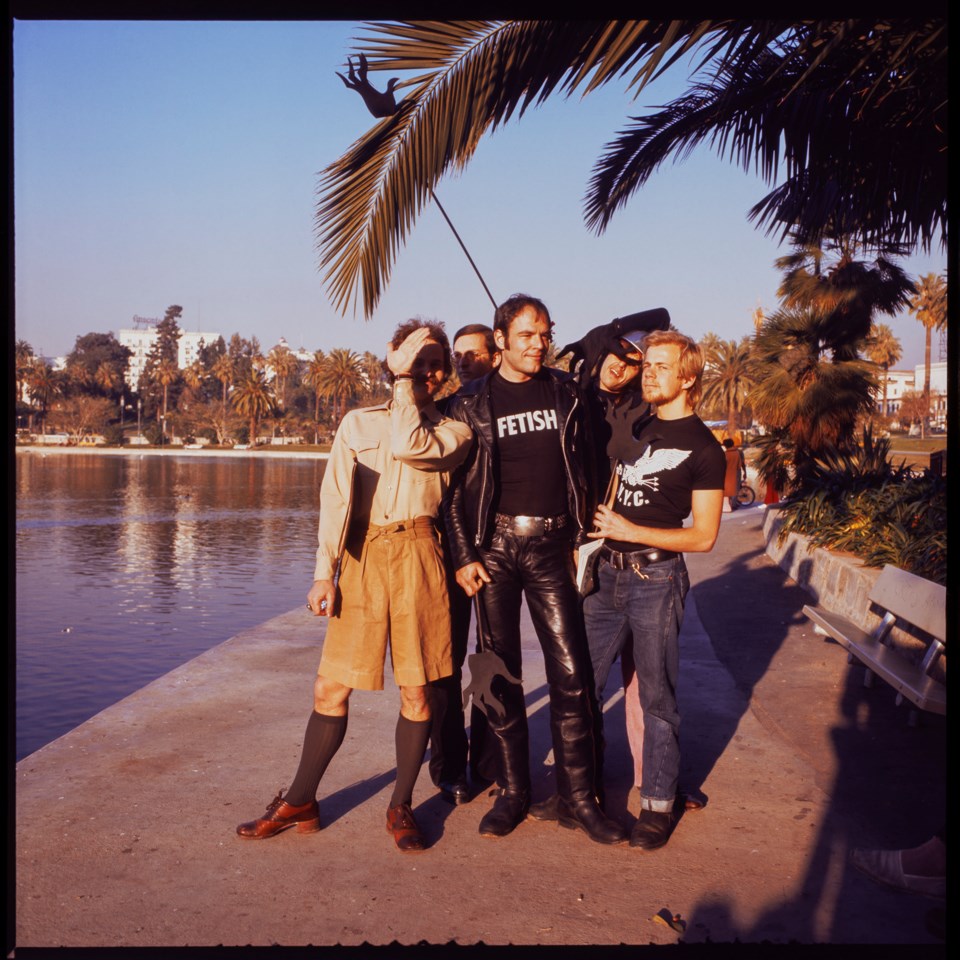

“Many of them sort of overlap,” Sawyer said of the exhibit’s sections. “They’re really built around networks and scenes. And that's one of the really important things we wanted to show. … Within artistic communities, [zines] were not only tools for creative output, but also ways to network with other artists.”

The medium’s prevalence was enabled by Xerox’s user-friendly copy machines, released in 1959, which made printing and collaging cheap and accessible.

Created and distributed independently of established media outlets, zines are inherently channels for subculture and many zines included statements that read like manifestos, said Joseph, cementing their status as a social and political force.

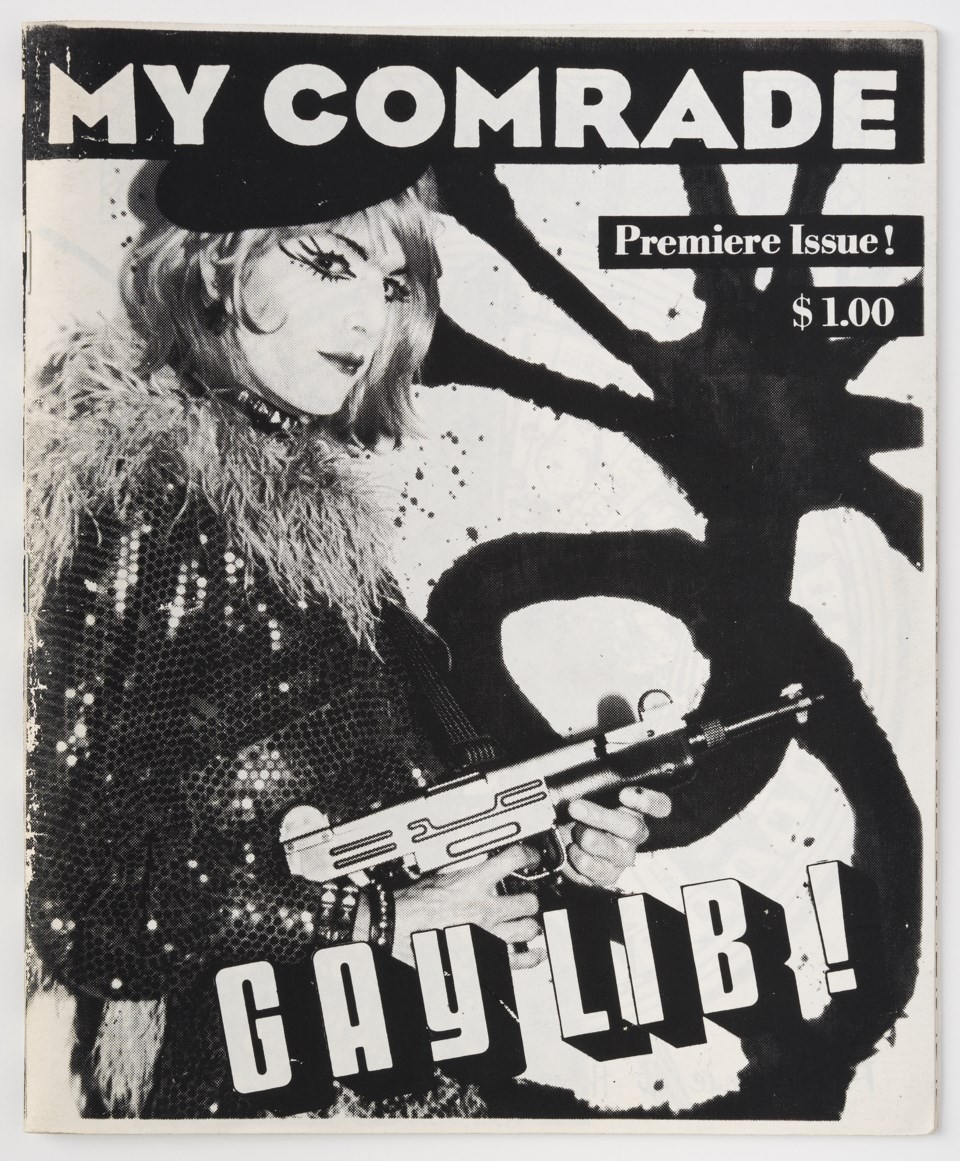

Zines made by and for LGBTQ+ people and women seem to dominate the collection. The exhibit emphasizes marginalized artists whose self-published periodicals allowed them to bypass barriers and control their representation.

“Artists turned to zines often to challenge what they saw was an existing orthodoxy or a tired institution or something that excluded them,” Joseph said.

During the 1980s, some LGBTQ+ artists used their periodicals to spread awareness of the AIDS crisis killing their peers.

“Many of these zine makers that we're looking at did produce art and zines that addressed AIDS awareness in various ways,” Sawyer said. “Joey Terrell did [the zine] ‘Homeboy Beautiful’ in the 1970s, but he did zines in the late 1980s that addressed HIV/AIDS."

One of Terrell's zines on the subject of AIDS, which contains a gay slur in the title, is "much more activist in its orientation,” Sawyer said.

The Brooklyn Museum has commissioned essays to accompany the collection from several current writers and zine-makers, like Mimi Thi Nguyen, who compiled the zine “Race Riot” in the 1990s as an ode to punks of color during the Riot Grrrl movement.

“It's going to have a lot of stuff, and a lot of energy, and music and things,” Joseph said of the collection. “You could come to this show as a card-carrying art historian, and go through, and get an alternate history of the last five decades of art practice.”