By: Nolan Jones, Mills College

The richest men in hip-hop never finished college.

Jay-Z â" who is regarded as hip-hopâs first billionaire â" never graduated from high school.

Kanye West â" who is considered hip-hopâs second billionaire â" was a college dropout, as he titled his debut album.

So was Dr. Dre â" another hip-hop icon and a near billionaire â" who left college after just two weeks.

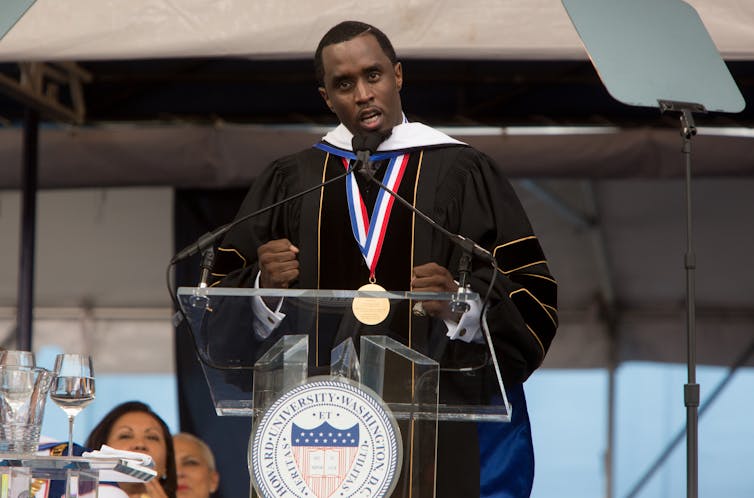

Ditto for Diddy â" now known as âLoveâ â" who dropped out of Howard University after two years.

Despite their lack of college degrees, these four men â" who are currently the richest rappers in the world â" have all taken a keen interest in higher education.

Dre, for instance, along with former record producer Jimmy Iovine, donated US$70 million to the University of Southern California to establish the USC Iovine and Young Academy, which focuses on arts, technology and innovation. The pair are also seeking to open a similarly themed high school in Los Angeles in 2022.

Diddy in 2016 donated $1 million to Howard University to help students who were struggling to pay off their student debt.

West has, at least historically, made education a central theme of his music. He also donated money to fully cover the college tuition of George Floydâs daughter, Gianna Floyd.

Jay-Z has created a scholarship foundation that has sent students to study abroad and has also â" along with his wife, Beyoncé â" donated $2 million for scholarships to support students at historically Black colleges and universities.

Whatever one makes of the fact that these men â" who all turned their backs on higher education decades ago â" would turn around and use their fame and fortune to invest millions of dollars in a college education for others, their stories represent only a glimpse of hip-hopâs complicated relationship with education.

As one who studies the use of hip-hop in educational settings, I have identified at least three ways hip-hop views formal education.

1. Schools are anti-Black

A 2005 study concluded that âfrom the perspective of rap music, the [d]iscourse of education is largely dysfunctional when it comes to meeting the material, social and cultural needs of African American youth.â

Perhaps no rap group has expressed this view more clearly â" and scathingly â" than dead prez, who were inspired by their high school experience to conclude in a 2000 song titled âThey Schoolsâ that: âThey schools canât teach us sh-t.â

Notably, it wasnât education that dead prez despised, but the racist manner in which they saw it being delivered.

As stic man â" one half of dead prez â" recited in the song:

I tried to pay attention but they classes wasnât interestinâ They seemed to only glorify the Europeans Claiming Africans was only three-fifths of human beings

Dead prezâs critique of public education was by no means the first time a hip-hop artist called out American education as racist.

Much like the English rock band Pink Floydâs cynical lyrics âWe donât need no education / we donât need no thought control,â many of hip-hopâs pioneering artists depict mainstream education as being designed to miseducate and program its students.

In 1989âs âYou Must Learn,â KRS-One suggests that schools should use a more culturally relevant approach when he raps, âIt seems to me that in a school thatâs ebony / African history should be pumped up steadily, but itâs not / and this has got to stop.â

In 2017âs âBlack Still,â Scarface raps: âOur kids educated by the enemy / And they donât know sh-t about their history / Cause they ainât teaching that in school.â

In their own way, these lyrics highlight frustrations with mainstream educationâs lack of a viable ethnic studies curriculum, which has proved to foster cross-cultural understanding, self-respect and diverse perspectives.

2. Schools donât teach self-reliance

Many rappers have called out public education for failing to emphasize self-reliance and how to build wealth in a capitalistic society. For instance, in his 2015 song, âFly,â the rapper Hopsin recounts how teachers wrongly tried to make him think that going to school is the only way to succeed.

Hopsin raps, âI was taught education is the only way to make it / Then howâd I get so much money inside my savings? / My teachers never saw the heights that Iâm f-cking aiming / Did the man who invented college, go to college? Hm, okay thenâ

A 2007 study found that hard-core rap âsupports a strong capitalist ideologyâ and that high school students in a New York City high school found this ideology âattractive because it supports their dreams and expectations of a successful and prosperous adulthood.â

This is one of the reasons that the entrepreneurial messages of rappers like Nipsey Hussle, 50 Cent and Master P tend to resonate.

A few prominent rappers also speak to building wealth. In 2017âs âThe Story of OJ,â Jay-Z speaks about generational wealth.

âFinancial freedom my only hope / Fâ"k livinâ rich and dyinâ broke / I bought some artwork for one million / Two years later, that shit worth two million / Few years later, that shit worth eight million / I canât wait to give this shit to my childrenâ

When rap artists find success, they often flaunt it in the face of former teachers who were naysayers â" offering them a sort of âlook-at-me-nowâ clapback by calling attention to their triumph despite a lack of formal education.

For example, the first words in Notorious B.I.G.âs 1994 song âJuicyâ were âYeah, this album is dedicated to all the teachers that told me Iâd never amount to nothinâ.â

While such braggadocio appears to focus only on the financial aspects of success, the lyrics reflect a deeper issue of how traditional schooling stifles the imagination and creativity that power entrepreneurial interests. In this paradigm, teachers are often cast as dream killers.

For instance, in âR.I.C.O.,â a 2015 song, Meek Mill raps: âFor my teachers that said I wouldnât make it here / I spend a day what you make a year.â https://www.youtube.com/embed/EgRrxFsX538?start=102

Nevertheless, Meek Mill announced in 2016 that he had enrolled in college because âbeing educated makes you money, and I like making money and taking care of my family.â More recently, in 2020, Meek Mill announced that he and Michael Rubin, a co-owner of the NBAâs Philadelphia 76ers, were teaming up start a $2 million scholarship fund for students in Meekâs hometown of Philadelphia.

3. Education is still a viable plan

When hip-hop was just beginning to go mainstream in the 1980s, there was an abundance of rappers who urged listeners to pursue education after high school. For example, Run DMC, in the classic 1984 song âItâs Like That,â rapped, âYou shouldâve gone to school, you couldâve learned a trade / But you laid in the bed where the bums have laid.â

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Similarly, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five rapped in a classic 1982 song âThe Messageâ: âYou say Iâm cool, Iâm no fool / But then you wind up dropping out of high school.â

L.L. Cool J rapped in 1987âs âThe Breakthroughâ: âSo get your own on your own / itâll strengthen your soul / Stop livinâ off your parents like youâre three years old / Instead of walkinâ like youâre limp and talkinâ yang about me / Why donât you take your monkey-ass and get a college degree?â

But much has changed since the 1980s. According to one study, in the past three decades, instead of closing the racial wealth gap for Black college grads, college debt and unemployment have expanded it.

Be that as it may, some rap artists, such as J. Cole, still view college as a viable backup plan. In 2007âs âCollege Boy,â Cole raps: âAnd if this rap sh-t donât work, Iâm going for my Masterâs.â

Hip-hop education has already proved it can provide both cultural relevance and improved academic performance. As one study suggests, if implemented in the right way in a classroom setting, âhip-hop can be a powerful tool to engage youth of color.â

In short, the blending of hip-hop culture and education has the potential to reshape schools in a way that works for everyone.

Nolan Jones, Adjunct Professor of Education, Mills College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.