Not Enough Government Support

In her letter supporting Gov. Kathy Hochul’s “Drinks To-Go” proposal, President & CEO of New York State Restaurant Association Melissa Fleischut said that, “more than 27,000 New York restaurants, bars, and caterers applied to the Restaurant Revitalization Fund, which provides assistance to restaurants and bars affected by the pandemic, asking for more than $9 billion in lost income from 2020 alone. Only 35% of those who have applied received funding.”

The Small Business Association (SBA) offered COVID-19 relief options, but analysis of the Census Bureau’s Small Business Pulse Survey found NY State among the places with the lowest Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) acceptance rate in the first round of funding (32.1%).

“NYSRA continues to work hard to support and advocate for restaurants as they combat supply chain issues, face sky-high inflation and grapple with ongoing workforce shortages,” Fleischut said. The organization has been calling for federal financial support since 2020. She said that the “NYSRA made sure restaurant operators were heard at all levels of government… [and] served as a trusted informational resource for restaurant owners on continually changing state guidelines and helped connect them with available grants and fundings.”

Unfortunately, the support failed to reach many.

A dataset last updated on March 27, 2021 compiled by Ryan Smith and Susan Roe from California State University shows over 410 GoFundMe campaigns from restaurants in New York State during the months of January and February 2021. 87 of them were in Brooklyn. Of those, 19 have permanently closed. That’s a 22% closure rate, higher than the estimated closure rate of 16.6% from the National Restaurant Association survey of the restaurant industry in the state in late 2020.

As BK Reader went through the long list of campaigns to reveal this statistic, we found hope, despair, sometimes just nothing in the GoFundMe descriptions, as if the owner didn’t have words to describe the situation that they were in.

Joseph (Bub) Adewumi’s Amarachi posted his GoFundMe page in late 2022 is one of those that went to GoFundMe with hope but left with a mix of gratitude and despair. In one of his updates from Jan. 24, 2023, he wrote: “The continued outpouring of support has kept us going and we are so thankful for the money, the visitation and the calls. As I write this I am really tired, and all this stress is affecting my health but any good news really matters.”

Then in an update on February 10 he wrote, “I’m afraid the clock has run out on us … the walls are closing in.”

Adewumi had applied for multiple small business relief SBA loans. But inflation, changing patterns in the way people dine, supply chain disruptions, increased labor costs, and higher rent ultimately required Adewumi to turn to the Internet, his patrons, and supporters for help.

Adewumi’s GoFundMe campaign only raised over 10% of his goal. Adewumi recently posted an update that reads, “I just want to personally thank everyone who has contributed to our efforts to remain at this address, but unfortunately, we have not raised enough to satisfy the requirements to stay. Our journey at this location is coming to an end.”

Similarly, Kirk McDonald and his wife Shawanna went to GoFundMe to save their restaurant The Southern Comfort. On Feb. 2 2022, News12 went to their place to tell their stories. On Feb. 7, an optimistic update came from Kirk, “From the bottom of our hearts, we would like to say a huge Thank You to everyone who has donated and or shared! / We still have a long way to go but we’re trusting and believing to meet our goal. / Continued blessings to you!”

BK Reader went to their place in an attempt to also tell their story, but this time the door was locked, the inside emptied but for a few pieces of dust-covered furniture. They raised only $14,600 over a $40,000 goal.

Rent was required in full for the McDonald’s throughout the entire pandemic. Adewumi took on a series of high-interest loans in hopes for better days, which ultimately became the thing that left him feeling “never more sick in his life.” He admitted to BK Reader that he and his family were “optimists to a fault.”

“And then you realize that you’ve been taking out a lot of loans hoping things will pick up and you can’t take out any more loans and the government isn’t offering any more assistance.”

The Southern Comfort was unable to receive public funding. Brooklyn Moon’s Michael Thompson said he “didn’t get a cent from the government.” Governmental assistance was a common theme.

New Variants, Same Outcomes

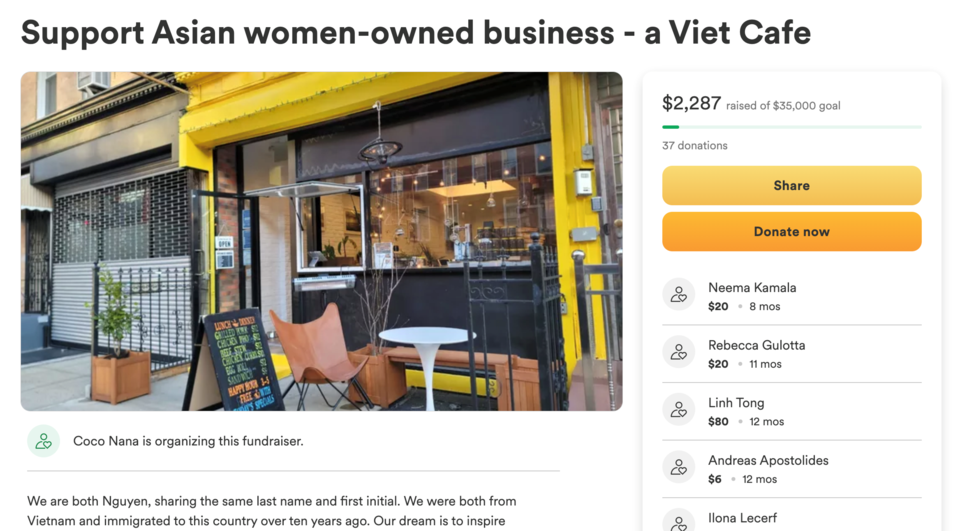

Hannah Nguyen, owner of a Vietnamese coffee and bánh mì shop called Coconana found herself opening a GoFundMe when COVID-19’s variant, Omicron, hit in the winter of 2021-2022. Having started the cafe in late 2021, her crowdfunding stopped at $2,287 out of the $35,000 goal.

Despite the unsuccessful GoFundMe campaign, Nguyen’s restaurant saw an uptick in customers during the summer months, and found itself thriving. That’s when a string of bad luck started happening to her.

“My landlord started changing his terms on me, and started causing me problems. He made up excuses about the neighbors complaining about me; he wanted me to fix the exhaust system that the last tenant had altered, which would cost $7,000; and since I only did a one-year lease, he asked me for another three-month deposit when it was time to renew and wanted to raise my rent by $1,500 per month.”

Nguyen ended up having to close her old location and move to a new location at 390 Social on 5th Ave. “And he’s still charging me for half of the property tax and then the water bills. It was pretty much one of the very rare times that I actually ended something on a bad term with somebody.”

Dana Morrissey, the owner of 390 Social, where Coconana now resides, and Chela, a Mexican restaurant where tortillas are freshly pressed, said that there’s no protection existing for business owners. “So when your lease expires, you’ve put in significant money to improve things and there's just no guarantee that they’re not gonna just take all of your improvements, kick you out, and then try to rent it to somebody for a much higher rent. We’re seeing that across the board.”

The Commercial Tenant Harassment law does not affect the landlord’s ability to “lawfully terminate your commercial lease, refuse to renew or extend your lease, or to reenter and repossess your commercial property.”

When asked if she applied for SBA loans, Nguyen mentioned that during the most difficult months of her business, she wasn’t eligible for any governmental loans. Her restaurant needed to be open for at least a year to be eligible for loans, and having opened in November 2021, she needed to wait till late 2022.

“Every time I applied for the SBA loans, there’s always something [that went wrong],” Nguyen said. “When I was about one year in, I applied. They were just about to approve and I had to close my shop. So, because I closed my shop, they said that you wait another year. At one point, I needed to have three bank statements before they could approve me for something.”

Morrissey added, “Which is kind of ironic, right? If I had money in my bank, I wouldn’t have come to you.”

Sellers of predatory high-interest loans, the same ones Adewumi was forced to take out, began to emerge for those small businesses owners in need of emergency funds. Legal “loan sharks” became a big business during the pandemic, after so many owners were unsuccessful in procuring any financial help from any government agencies. One also approached Nguyen offering an interest rate of around 45% per year, she said.

But businesses do take them out of desperation, Morrissey said, because of the pressure to keep the business going even without profit. “When you hit a snag, those predatory loans actually seem like an easier option, compared to the SBA or other places that are much more conservative,” she said. “And they wind up in this horrible debt cycle that eventually sucks a lot of businesses under. I don't think people talk about that enough.”

The city said it’s addressing Nguyen’s concerns. City Councilmember Julie Menin (NY-5), chair of the NYC Small Business Committee, was against the SBS’s decision to reduce the federal funding for small businesses from 64.6% to 29%. She said that the City Council “will be advocating for increases to the budget for the New York City Department of Small Business Services, so we can efficiently aid our small business owners and Minority and Women Owned Businesses (M/WBEs).”

Crowdfunding Becomes a Final Option

Most of the restaurants that turned to grassroots organizations like GoFundMe did so because their federal-, state-, and city-directed pleas were not answered. But crowdfunding platforms are ecosystems reflective of American society.

Research on medical and health care support pleas on GoFundMe shows that current financial distribution in the U.S. along with racial biases heavily impact the likeliness of a campaign meeting its goal. Restaurants on GoFundMe are predominantly Black- and minority-owned; many of them struggled to meet their goals.

Adewumi said starting a GoFundMe was very humbling, “because people always think, ‘Oh, they’re a failure.’”

“But it’s not really a failure,” he said. “You have to look at all the factors that contribute to why a person is crying out for help.”

And perceptions– people’s individual perceptions, that is– play a big role: While for one person, crowdsourcing campaigns might signal opportunity and salvation, for another it might signal the beginning of the end.

It was the latter perception, said Nguyen, with her business. Her GoFundMe was featured on Patch (without her knowing), but she believed it worsened her situation: “People would pass by but would ask if I’m about to close down my shop instead of coming in,” she said.

Does it come down to how much one’s impact is worth in their community? For the business owner, is reciprocity not a fair expectation?

For Thompson and his restaurant Brooklyn Moon, giving so much back to the community over the past 20 years-- and especially during the Pandemic-- makes him feel that his current goal of $200,000 should be doable, although, as of this date, he's only been able to raise a little over $5,700 since January 2023:

“I’m not asking one person for this amount of money, I’m asking a community,” he said. “I’m not a greedy man … As many people have known what I’ve done, I figured it would be taken care of in no time.”

Even if only 23% of all crowdfunding efforts reached their goal, 100% of the restaurants that used the site did receive something. And any help is still help.

But to count on Crowdfunding as a reliable resource? It’s hit or miss. And at the end of the day, no one owes you anything.

For restaurants fighting for survival during and post the pandemic, can we view the success of crowdfunding platforms as a referendum on the business’s impact in their community? Not necessarily.

Is their dependence on crowdfunding a referendum on the government’s own gaps in support for small businesses during this crisis? Perhaps.

Or is the effectiveness of crowdfunding for restaurateurs a referendum on the economy and the everyday citizen’s financial ability to give? Also possible.

Whatever the reason is, what we do know for certain is that the harrowing state of the restaurant industry is a referendum on the COVID-19 pandemic– and the havoc it has wreaked on us all.

Check out Part 1, the introduction of this series, that provides an overview of the state of the restaurant business in Brooklyn, and how some restaurant owners had to pivot to keep afloat.