Everyone was welcome to his table. Michoel was always up for socializing. It was never too late. He was never too tired. In the last years of his life, he was still making friends.

By Amy Baily

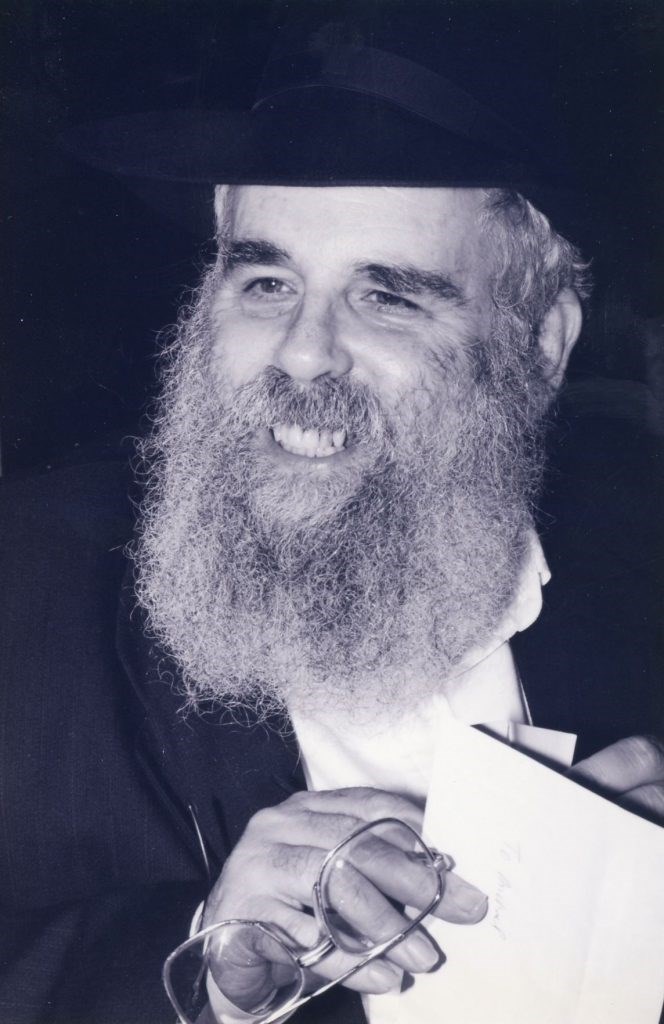

Some 200 people gathered last week at Nemes Hall in Crown Heights to honor the memory of Michoel Behrman, a longtime resident of Crown Heights and a member of the Chabad movement.

Michoel was born in 1939 in Hawthorne, New Jersey, and he explored the whole world before coming home to Crown Heights, where he spent the last four decades as a substance abuse counselor and civic activist. He numbered among his friends and loved ones. People all over the social, professional, and political spectrum, and friends and family came from around the globe to mourn his passing.

As a child, Michoel accidentally stepped on Herbert Hoover's foot at a Yankees game, and the former U.S. President responded very unpresidentially. Perhaps this is when Michoel learned the difference between political and moral authority—throughout his life he demonstrated a steadfast irreverence for one and profound respect for the other.

In 1957, Michoel went to the University of Miami. Several of the friendships he made there would last the next sixty years, as would his education: he was by nature a seeker, explorer and student of the world, and would be for the rest of his life.

After leaving the University, Michoel sold real estate. He sold insurance. He worked in the film industry. In the late '60s, he traveled the world—often by cargo ship—visiting India, Morocco, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran along with the countries of Europe; he lived for months at a time on beaches in Ibiza and Goa.

"We bonded in the 60s, which was a pretty tumultuous time. Michael was intent on finding himself. We would sit up all the night and talk about who we are, why we are here and is there a god," said his lifelong friend Richard Druz.

When he came home to the United States, Michoel returned to the film industry, working his way up to Second Assistant Director credits on Bananas, McCloud, All my Friends on the Shore, and he even worked briefly on The Godfather. At the same time, Michoel found himself exploring Judaism. Decades later, he would tell his son Yaacov, "It wasn't like I was attracted; it was like I was pointed in a direction. It was not an intellectual decision."

He was often in the company of artists—painters, musicians, actors, creative thinkers and doers of all disciplines. He was a close friend of Mason Hoffenberg, who introduced him to Richard George Manuel. He was also friends with Ronnie Boykins, Philly Joe Jones, and Ornette Coleman. It was in these Greenwich Village circles that he met underground filmmaker and artist Zalman (Jerry) Jofen, son of a prominent rabbinic family from Poland. Their friendship would play a major role in Michoel's journey towards Judaism.

That journey, in turn, influenced his career: When the opportunity came knocking for a job working on The Chosen, Michoel thought about it but eventually turned it down, feeling that the story didn't represent the authentic Judaism, which he came to respect and love.

Years later, when asked if he regretted not working on it, he laughed. "No, it was a terrible movie." He realized there was no place left for him in the film industry when he was offered a six-week job on an island in the middle of the winter, "the perfect job, good pay, good per diem, but Saturday work."

In the early 1980s, Michoel owned a used book and record store with a partner. In a box of dusty books brought in for sale, he uncovered an old Talmud. He lifted it up and started to weep. This is what I should be doing, he thought, studying these books full time.

Wherever he went, Michoel created a sense of community and shared enterprise. His earliest forays into community organizing were in Summit, NJ, where his family moved in 1951. A baseball fanatic—President Hoover notwithstanding—he would roam the neighborhood, younger sister Jill in tow, rounding up enough kids to form two teams and get a game going.

In Crown Heights, facing a real but often unacknowledged threat to residents from illegal drugs, visionary Rabbi J. J. Hecht tapped that ability when he recruited Michoel to start Operation Survival, a drug prevention program. Even when some opposed him on the grounds that drawing attention to substance abuse would hurt the community, Michoel persisted, and, with just a handful of people, went on to save hundreds of lives over the years.

Scott Silberman remembers being hauled into Michoel's office by his parents in 1995. The overwhelmed elder Silbermans began talking rapidly to Michoel, but he cut them off, saying, "I want to hear from your son." Twenty-two years later, Scott still cherishes the hour that followed, which he spent in private conversation with Michoel. Michoel, he says, was the first person who ever listened to him, who heard him and responded with empathy, sensitivity and kindness. To this day, he credits Michoel with his recovery, which permitted him ultimately to marry, have five children, and repair his relationships with his parents and sister, but Scott initially resisted treatment. He remembers Michoel negotiating with him: "Just go to rehab for two weeks, and then see," he said. It worked, Scott said, because, in that short period of time, he came to trust Michoel so much.

That was the power of Michoel's ability to connect with others.

Michoel's ability to connect was essential again in Crown Heights in the aftermath of the riots in 1991. Having been attacked himself in the events, Michoel redoubled his investment in the community, attending emergency committee meetings and organizing events working to protect the residents.

"Uncle Mike was a man you could know well, but about whom you could always learn more. He could be serious. He could be side-splittingly funny. He was an inexhaustible raconteur and a good listener. He was both reverent and irreverent. He was deeply religious but to him, Judaism wasn't just about following the rules; it was about analyzing, dissecting, deliberating, and laughing, when he discussed the rules," said his nephew Evan Baily.

Everyone was welcome to his table, and no matter how under the weather he was, he always welcomed visitors to swap jokes and tell stories into the wee hours. Michoel was always up for socializing. It was never too late. He was never too tired. In the last years of his life, he was still making friends—and they dropped by at all hours to spend time with him.

Most of all, Michoel cherished his family: his wife, Sarah, who passed away in 2013, his four kids, nine grandchildren, one great grandson.