"The Art of Seeing" by Michael Milton

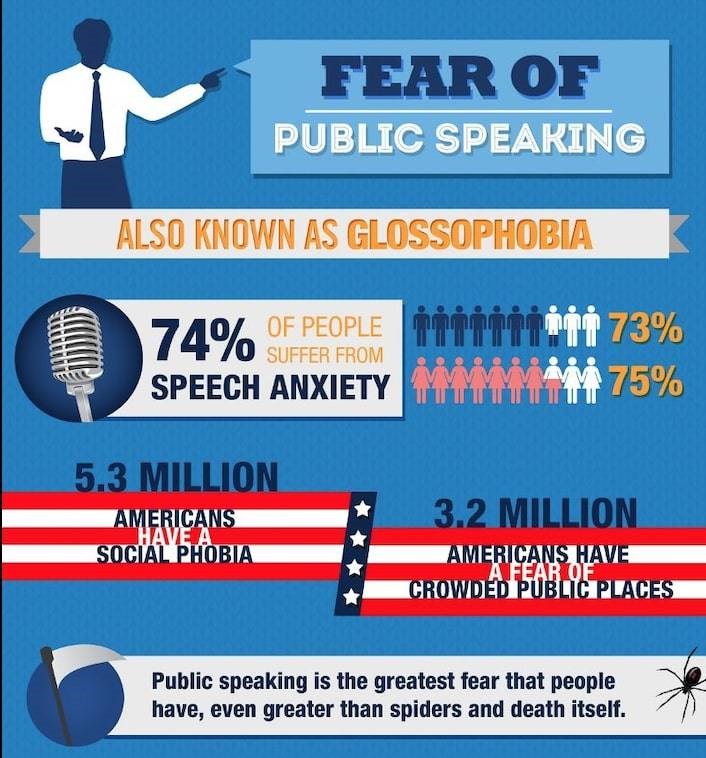

I joined Toastmasters over three years ago. For anyone who isn't familiar with this organization, Toastmasters is an international club which guides members towards a more direct method of public speaking, helps improve communication and builds leadership skills.

Truly, these skills are only the tip of the TM educational/social-networking iceberg. TM has helped me in so many ways, most specifically being able to better relax not only in casual conversation but also in more formal "speechifying" settings.

Next time you watch the nightly news, listen for how many "ahhs," "ummms," "you knows" and other filler words are inserted into the reportage of guests. Then, notice how the more polished newscasters seldom if ever rely on them. The result of a crisper, seamless delivery creates a positive uptick in our perception of the speaker. These speakers have learned to hold our interest by matching their stream of thought to a well-paced flow of conversation.

TM will help you polish your delivery in any situation and give you a more intelligent and compassionate demeanor. And there will be nothing artificial about your new speaking comportment.

There are a number of clubs available in Brooklyn. Simply Google Toastmasters International. If you feel you are being held back in business, in love, in friendships by a halting communications style, this is something you may want to check out.

What follows here is a speech that I gave recently at a TM event about how I discovered my speaking voice three times!

********************

Mr. Toastmaster, Fellow Toastmasters and Honored guests,

what do Toastmasters, immigration and brain surgery have in common?

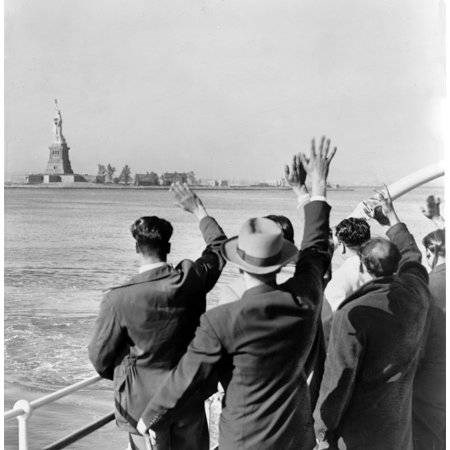

The word that comes to my mind is 'bravery.' Bravery is the mental strength to face danger. Bravery is what it takes to leave one's country of birth and move to another land. Bravery is a part of what is needed to survive a life-threatening health situation. And, it is bravery that helps all of us to come up to this podium week after week.

Five.

Count them, five years of Latin. Four in high school and one year in college to fulfill my foreign language requirement. If you hadn't already heard, Latin is a dead language. Oh, don't get me wrong. Latin is a great help if you happen to want to be a priest or you enjoy crossword puzzles.

My reason for taking Latin was silly. I wasn't, in fact, being very brave. I didn't want to wrap my mouth around an accent. Latin, as it works out, doesn't require a special accent; it sounds as archaic when spoken by an Englishman as it does by a Frenchman. I had enough other issues on my post-pubescent plate; I didn't want to add people laughing at me struggling with a German or Italian accent.

Many years later (still only speaking English), I attended my first Toastmasters meeting. I was especially moved hearing speeches by so many people for whom English was their second language. Here were newly-minted Americans being more serious about their adopted land and their new language than many native-born Americans. And seemingly having no issues with their own native-tongued accents.

It was then, that I realized that I had, at one point in my life, been a stranger in a strange land, having to learn new customs, to fashion a new way of thinking, and to adopt, if you will, a "new" language.

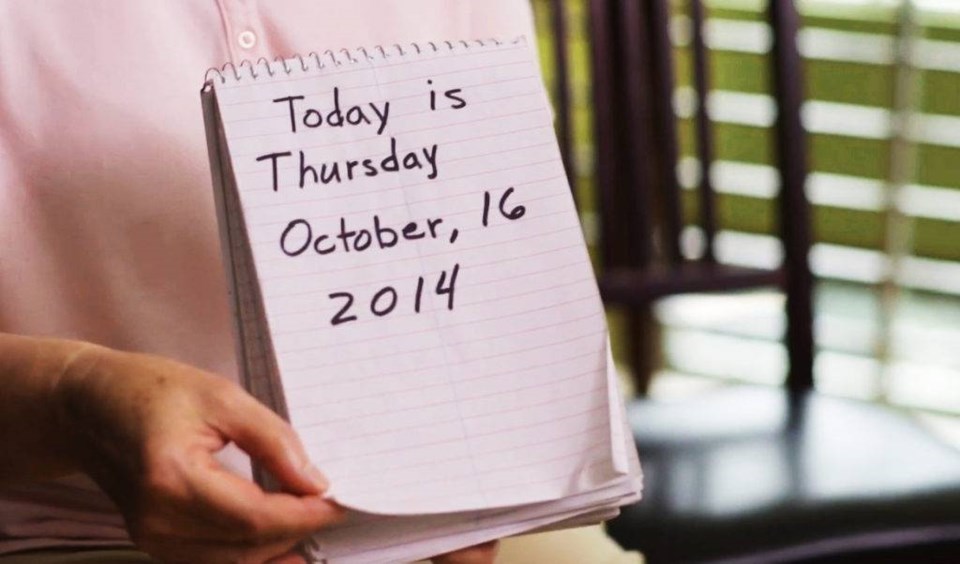

In 2003, it was reported in a New York City newspaper that a man trying to cross West 57th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues had a seizure. Halfway across the busy street, he began walking in queasy circles, stopping traffic on the eastbound lane until a policewoman grabbed him by the arm and pulled him to the sidewalk.

That man was me, and after being rushed to the hospital, it was discovered I had something called an AVM, an arteriovenous malformation. A small vein in my brain had worn out and was spilling blood. I would need surgery.

I was told the bleeding was taking place around the area of the brain that controls speaking. A very possible outcome of surgery was that I would lose my ability to speak altogether. I was afraid. This time, I was also brave. I said yes immediately to the surgery.

Post-op, I couldn't speak for a couple of days. Slowly I gained back some words. Speaking felt foreign, English as much another language to me as, I suppose, it feels to someone first taking it up.

I was forced to begin thinking in much smaller sentences. "Where is the bathroom?" "How do I get to the bus?" "My name is Michael." Therapy was a repetitive process to reorganize the brain, building new neuron passages towards a new way of speaking. I repeated lessons like: "A tree toad loved a she-toad who lived up in a tree. He was a two-toed tree toad, but a three-toed tree toad was she." Or the perennially popular, "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers."

I felt stupid when I couldn't express a simple thought. I was embarrassed by the sound of my voice, thick and slow. What must it be like to come to a new land—intelligent and clever at home—but here feeling dull and alone, not understood in the full richness of one's native tongue? In a way, I felt like an immigrant; I had left my past behind on the operating table and now searched for a new home, a new path, with the challenge to relearn a once mastered language.

I don't claim to really know the full extent of bravery that it takes to literally pull up roots and move on. Nonetheless, I now understand why I was so moved my first day in Toastmasters, a room in which participation requires great bravery from each and every one of us, whatever our original language.

In a way, when we speak at a meeting, we are "immigrating" from the person we were when we walked in the door towards the person the spoken word is helping us create. I have learned how to speak three times: in school, in recovery from brain surgery and now again at Toastmasters where my joy in communicating with others continues to grow.

Bravery in immigration. Bravery in facing surgery. Bravery here at Toastmasters.

Perhaps more than bravery, this speech is really about admiration; I heartily acknowledge all of us for the risks we take each week at our various club meetings. I respectfully recognize my bold native English speaking friends who have tackled a second or third or fourth language. But especially, I bow to the bravery of my Toastmaster brothers and sisters -- Indian, African, Chinese, Italian, Japanese -- who have challenged themselves to become effective communicators in a language they were not born to.

This is for you.