During Anti-Ableism Month, BK Reader explores the equity issues around Open Streets for the elderly and disabled residents of Brooklyn.

Few people would argue against the value of The Open Streets program in New York City the summer of 2021.

New York City was emerging out of what seemed like the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic. And, at the time, nearly everyone was in need of safe open spaces, fresh air and a reason to feel good again.

The program — which transforms one to four short blocks of streets into closed-off pedestrian walkways — allows for a range of activities aimed at promoting economic development, community building and overall physical and mental well-being.

However, three years later, with COVID-19 deaths down to less than .1% globally (which is .001 of total cases), according to the World Health Organization, many Brooklyn residents are ready to resume their lives before COVID, which includes doing away with Open Streets.

The call to end the program comes from residents most impacted by the streets being closed off, including the handicapped, the elderly, and some homeowners and storefront owners who need access to the parking that Open Streets eliminates.

“I know it’s an unpopular opinion to say you don’t want open streets today, but the ones who still want it are the people who don’t have trouble with mobility,” said Clinton Hill resident Claude Graves, 63, at a September 29 meeting in Clinton Hill. "Those same people who want to leisurely hang out or ride their bikes on the street can go to Prospect Park. It's discrimination to ignore the needs of the handicapped and disabled so that able-bodied people can be convenienced.”

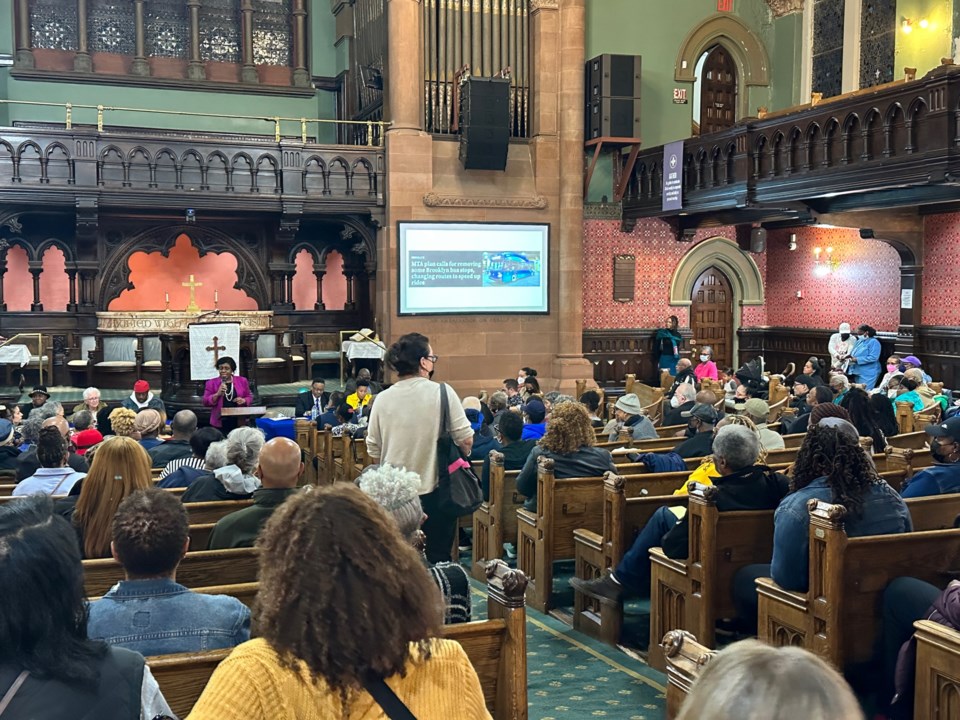

The meeting took place at Emmanuel Baptist Church, led by the church’s head pastor Rev. Anthony L. Trufant, along with members of NYC Access for All, a non-profit American Disabilities Act (ADA) advocacy group fighting for equal access on NYC public streets.

“But we're not here today to hear from me,” said Rev. Trufant. “Rather, we’re here so that you can hear from people who can share their respective experiences and give you insight into issues that you may not know [about].”

More than one hundred residents gathered at EBC for the meeting, several elderly and a few dozen with canes, walkers and wheelchairs. Also attending were a number of concerned able-bodied residents, including the actor Malik Yoba, an EBC member.

The groundswell of residents around the issue of street access for all began to take shape in 2021, a year after COVID-19’s height. On April 24, 2023, 12 New Yorkers sued the City of New York for ADA violations on Open Streets — Charles v. The City of New York, et al. Their complaint was that for the last three years, politicians have gone along with the city and other pro-bike organizations to expand open streets while violating the civil rights of seniors and people with disabilities in an effort to make biking a priority.

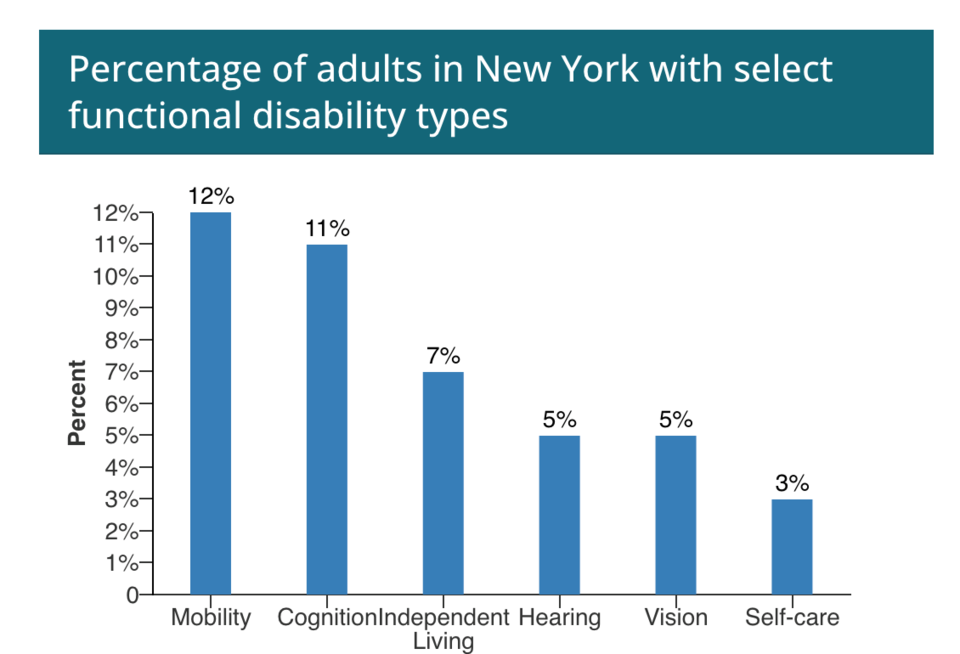

According to the CDC, one in four New Yorkers (25%) report having some type of functional disability, while fewer than 900,000 New Yorkers (1%) ride a bicycle regularly, according to The City of New York.

“You know, to me, these bikes act like they’re cars, but it’s worse, because sometimes they don’t even follow the lights, the signals,” said Jennifer Logan-Davis, a 50-year resident of Fort Greene. She was at the meeting to represent herself and her mom, both of whom are disabled. While Logan-Davis walked into the meeting with a cane, she said her mom stayed home, because it had become so difficult for her to leave the house.

“I walk with a cane and now I’m experiencing vertigo,” she continued. “You know, we have to pay close attention to the lights when crossing with the cars. But these bikes will just shoot right by you and knock you over because those lanes weren’t there before.”

However, Marco Conner, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, an advocacy group that promotes initiatives to make streets safer, told The New York Times that the small risk from bicycles pales in comparison to the deadly risk from cars and trucks: "There is a false picture that has been painted of cyclists pitted against pedestrians, whereas both cyclists and pedestrians are vulnerable road users,” Conner said.

The meeting lasted almost two hours and provided an opportunity for a few participants to share their testimonies. Many of those who spoke felt that outside of these spaces, their voices were being ignored, amounting to what they see as ageism and ableism.

“If they wanted to block off these streets a few times a year to bring the community together, then okay,” said Graves. “But having the streets blocked off every weekend or even every day like over here on Willoughby, for the elderly and disabled, that means we are locked in the house because we cannot get to a car or an Access-A-Ride.

“That’s not right. The worst of the pandemic is over, and now we’re speaking out.”