We are being evicted and I am dismantling my library numbering thousands of books. Some of these books have been written by me, a larger number by people I know or have known. Most of them, like Christa Wolf, Judith Malina, Grace Paley, Alix Kates, Shulman or Brooklyn writer, Jan Clausen, who has just published a new book, I came to know because I first loved their books, and only then, or because of that, did we come to admire or to love one another.

Were it not for our eviction after decades so the house can be sold for top dollar by its absentee landlady, I would gladly have lived in this apartment the rest of my life, surrounded by these many books, and the new ones I voraciously buy (from independent bookstores only) especially when researching a new work of my own. The books have graced the ceiling-high living room shelves, been piled in stacks on the wooden bench near my bed and on the floor in my office, its walls made of bookcases jammed mainly with plays I have written and many more that I teach.

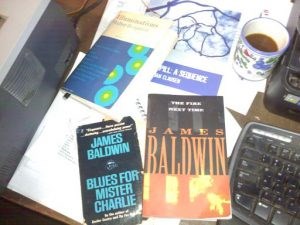

On my desk now (in the basement office I must vacate soon) are two books whose authors I did not know but whose essences feel as close to me as if we had lain together entangled in sheets. That's the thing about books, the tactile object that you can hold, and stroke, whose pages you can turn or turn down, whose lines you can mark with a pen reminding you when you look again what was important to you then. This is the problem I face: which books can I let go without letting go of something I desperately need—a memory, a time of life, an insight to which I must be able to return but can only do so through the pages of a particular book.

Soon after the landlady's lawyer brought the eviction notice to our door I went to the exact place on the living room book shelves where I knew I had put twenty-three years ago when we moved in Walter Benjamin's Illuminations. I needed to reread his essay "Unpacking My Library". I bought this book in 1974, so my handwriting on the inside cover tells me. In my circle, the downtown world of the avant-garde theater, we were all reading Benjamin, then, the German-Jewish critic who was the great playwright Brecht's great friend. Benjamin became known only posthumously; he killed himself in 1940 fearing capture by the Nazis.

I look through this paperback book, coming apart at the binding; I find the sentences I bracketed then. "For every passion borders on the chaotic," Benjamin writes, "but the (book) collector's passion borders on the chaos of memories." This is precisely the chaos I am in now as I do the reverse of Benjamin, then. I am not unpacking but am being forced by eviction to discard so many books and how do I know, how will I know until the deed has been done, which book I shall go looking for in the dead of night a year or two from now in a place I cannot yet imagine only to find that book has vanished from my life with all its attendant memories too.

Next to Benjamin lays James Baldwin, or rather a tattered paperback copy of his great play Blues for Mr. Charlie. In 1974, when I bought this book for seventy-five cents, I had just begun to write plays. Did I already know how much a mentor Baldwin would come to seem, for the force of his rolling rhythmic prose, his harshly uncompromising insistence on truth telling, his passion for justice would make his plays beacons to my own.

In The Fire Next Time Baldwin writes of his own early history with books, how on his way downtown from Harlem at age ten to the New York City Public Library, he was accosted and roughed up by two white New York City policemen who told him "the nigger" should remain uptown. Little did they know, nor did he, that they were assaulting one of America's greatest writers thirsting for the comfort of books. When I teach Baldwin's play, I watch my students wake up.

Through his stunning language Baldwin accomplishes the impossible. He creates before us the full brutality of American racism, in all its horrible sadistic and sexualized forms, then dives straight into the souls of its victims and resurrects them with all their courage and rage. Through words, Baldwin exposes but then undoes the terrible truth itself leaving us starring straight into a vision of another way, equitable and just.

Books by Baldwin and Benjamin will go where I go. But I return to the central problem I face: Dismantling a library is tantamount to casting off parts of the self. Letting go of a book is a form of amputation, for the book contains the experience of the life that was lived while reading and rereading it, and reading has often changed my life as it has the life of everyone who reads. Each book has a place in the "chaos of memories" that becomes what we know of ourselves. "You have all heard of people whom the loss of their books has turned into invalids," Benjamin writes. It does feel exactly so; from the too quick discarding of a single book I might carry forever the ache of a missing limb.