Who is the villain?

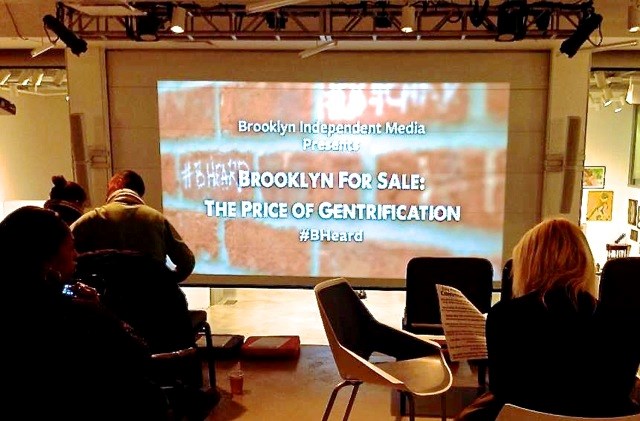

The question kept coming up at Brooklyn for Sale: The Price of Gentrification, a town hall meeting hosted at Bric by Brooklyn Independent Media, January 28.

But the villain was not in the room of mixed-race organizers, activists, teachers, council members, artists, who are renters and old-time owners, and all of whom agree that gentrification (or is it rather the organized displacement mainly of poor people of color to somewhere else) has to end.

The villain is an idea, an ethos, to which any and all of us might pledge our allegiance: that money is the measure of all things and whoever has it is a success. And if money can be made by throwing people out of their homes, that's just fine. The idea drives the street hustler and the Wall Street hustlers, alike. Yet, some of those who have invaded Central Brooklyn's turf were driven across the bridge as Brian Vines, the evening's moderator, pointed out, "by the tragedy of 9/11," looking for personal safety farther away from the seats of financial and real estate power, and, in the process discovering beautiful, places to live.

Therefore, there was some soul searching: Were the artists who started arriving in ethnic and black neighborhoods in the 70s (of which I am one) the original gentrifiers? What about the long-time black owners who are selling and moving down South? Or the flippers, like the people who just sold a narrow row house in Clinton Hill they had owned for eight years for 2.4 million, a neat profit of half a million, and have moved on to Bed-Stuy to buy and flip again? Then, there are the absentee landlords and ladies (one owns the house from which I was recently evicted) who rented for years at just market rate, doing absolutely no or bare minimum upkeep and are evicting long-time tenants in order to rent at high prices or sell for astronomical profits?

Then, there are the absentee landlords and ladies (one owns the house from which I was recently evicted) who rented for years at just market rate, doing absolutely no or bare minimum upkeep and are evicting long-time tenants in order to rent at high prices or sell for astronomical profits?

These are the neighborhoods, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Bed-Sty, Crown Heights, etc., that were red lined by the banks, deemed unworthy of investment, left to flounder and to pull themselves together, fix the neighborhood schools, form block organizations, patronize the local business, and send the children to college. Robert Cornegy, the Councilmember for the 36th District, Bed-Stuy, returning home with a master's degree has been accused of being a gentrifier, though he is actually a native son.

He worries that his own children will never be able to afford Bed-Sty when they grow up. Neil deMause, journalist, also on the panel voiced the same fear, where are his children going to live? Who will see to him as he ages? It has already happened to me, my daughter raised in Brooklyn and her new husband from Long Island, have had to move to San Antonio, Texas, where they think they might afford a house. Gentrification, or shall we call it displacement, rips families as well as neighborhoods apart.

Jherelle Benn, dedicated, young and energetic young organizer from Flatbush, told of a family she is currently trying help whose landlord simply lets the ceilings fall down on top of the children, not once, but more or less regularly, so that their mother fears for their safety. Once she moves her children out (but to where?) you can bet those ceilings will be fixed as the rent goes sky high.

There was another story deMause told about a family with two parents working, long-time residents of Crown Heights, who cannot find anyone willing to rent to families with children; the landlords would rather have an apartment shared by three or four working young professionals, instead—why bother with kids?

Everyone in the crowded auditorium seemed to agree with Ron Shiffman, urban planner and founder of the Pratt Center for Community Development: There is no sane public policy in place. Real estate interests; new, wealthy owners and investors run the game. They receive state and city subsidies on the promise that 20% of new developments will be "affordable housing" while 80% can go for ever-rising so-called market rate—again, affordable for whom, and market rate for what income bracket?

Renters, small business and long-time home owners who tend to charge more reasonable rents when they rent, be damned. No one with power is on the side of those who have actually lived in these neighborhoods and made them, now, such attractive places for the wealthy to move, or for people to park their money, without even having to live here. Every battle takes enormous organizing energy; each battle has to be fought again and again since public policy does not change.

Decisions about new development are made without community input. In Fort Greene-Clinton Hill, a land-marked district, we live increasingly in a moat: The cranes rise, stacking floor on top of floor in new high rises in a ring around us. Most of these new high-rise apartments appear to be empty, but many empty ones are owned as investments by absentee owners who receive the tax-breaks that ownership brings.

Then, there is this, as Shiffman and other panelists said: prices and rents skyrocket, while wages for the working and middle-class, for teachers, social workers, artists, police officers, those who actually contribute to the daily cultural and communal life of the city, have long stagnated.

We simply cannot afford to pay what the uber-wealthy can pay, nowhere near as much. But these streets have been our homes.

In the old days, no one made a distinction between owners and renters. Local owners, who live in their homes, wanted good tenants. Tenants were happy to be good; rents were affordable, space was ample; we agreed that our streets were beautiful. This was true even during the crack epidemic, even when street life was more dangerous than it is, now. We loved our mixed neighborhoods and looked out for our neighbors. Now, we feel like outliers; we watch the complexion of the neighborhoods changing as people of color "vanish" either to return down south or be pushed further out (to where?).

Is it racism and classicism at work? Seems to be, and no one could actively disagree—those of us in that room, that is. Though no one had a ready answer either, and people like Juan Ramos and Jherelle Benn have been organizing neighborhoods for years, winning small victories, building coalitions.

"If anybody were on the trail of the real villain," one of the panelists said, "it would be the whole capitalist system." No one stood up to disagree with that, either. Though it must be pointed out that all in the room were on the side of small, local business owners—it's the chain stores, banks and big rents that are driving small businesses out.

"What would ethical gentrification look like," Vines asked panelist Sharon Zukin, a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College.

"There ain't no such thing," Zukin replied. No one disagreed with her, either.

What do we do, now, that we have a progressive mayor and city council? Sane public policy in the public interest would be a start. Everyone in the room seemed to agree. At very least, there should be a 50-50 split between affordable units, and they should really be affordable based upon real incomes, and market rate units whenever a new development, with its government subsidies and tax-breaks, is approved.

This is a proposal approved by our Congressman Hakim Jeffries, by the way, but without a chance, at the moment, of being turned into actual policy. Then, too, the influx of money from investors who have no intention of making our neighborhoods home, should be halted. So should profits new owners are gleaning from properties, like AirBnBs. In an ideal world, there could even be a cap on the profit margins flippers and absentee landlords are allowed to make for owning but not maintaining and not staying in communities.

These solutions, reasonable and humane, fly in the face of the absent villains in the room: racism, classism, and, yes, unfettered capitalism.