By Jake Bolster

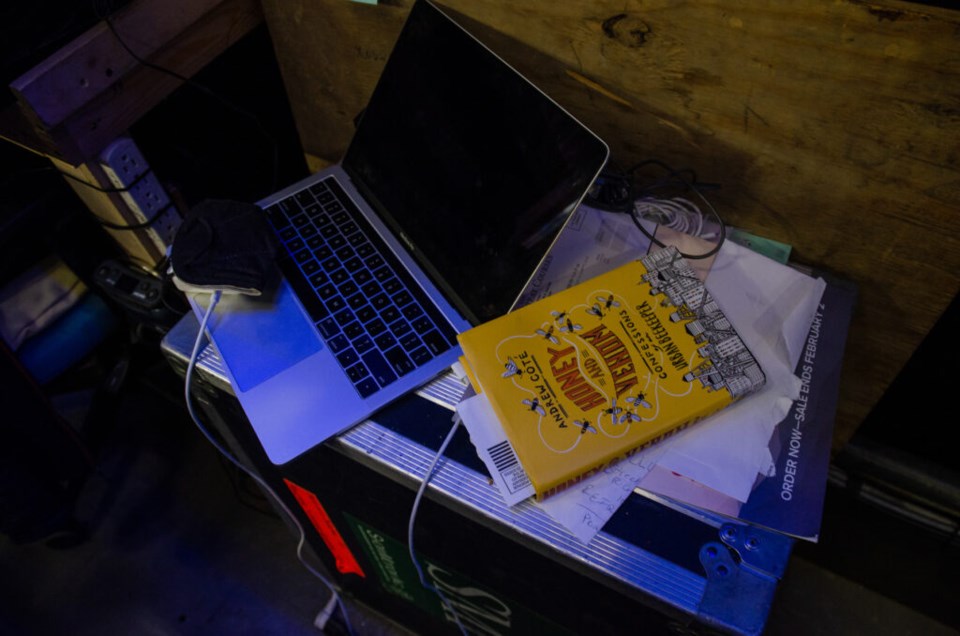

Operating a fly system in a theater on Broadway used to involve several crew members in the wings pulling ropes connected to rows of steel beams high above the proscenium arch. The ropes were counterweighted, allowing people to move elaborate set pieces, large props, or even people connected to the beams offstage safely and silently. In the age of automation, little has changed about the machinations of this process except that now it is a one man show. Stationed at a desk high above stage in the wings of the Hudson Theater, sits Tom Gordon, the theater’s House Flyman, capable of moving any number of set pieces without ever touching a rope. A necklace of red, blue, green, and yellow bulbs wraps around the stem of his monitor, each color corresponding to a chronological list of cues on his screen. Before each show, Gordon and the Head Carpenter run the cue list, communicating through headsets.

“It can be dangerous,” said Gordon referring to the speed with which the wire ropes, traveling inches from where he’s stationed, can sometimes move. “But nothing moves fast on (“Death of a Salesman”), so it’s not that bad,” he said, before adding, “no one’s up here with me.”

Gordon’s been working in the professional theater world for over three decades, from Broadway’s stagnation in the 80s to the industry’s racial reckoning and rebound from the pandemic in the 21st century. Against the sometimes siloed backdrop of Broadway—where the playwright writes, the director directs, and the actor acts—Gordon’s stories, hobbies, and long professional resume are the fruits of a labor rooted in a nimble sense of adventure, a testament to the many talents and interests of those working behind the scenes on a show.

In 1988, one year after he graduated college, Gordon went on a nine-month tour across Europe with “Sophisticated Ladies,” a show featuring the music of Duke Ellington, as an assistant carpenter. In 1992, during Hugo Chavez’s attempted coup d’état in Venezuela, Gordon worked as a crew member at a theater festival in Caracas run by the local theater company Rajatabla; he can still recall the sensation of tear gas from nearby protests seeping into his vision as he navigated the city. He’s been to Cuba twice, once in 1996 out of curiosity (“I live in a free country that's not allowing me to go certain places? That’s not free.”) and again in 2010 as a crew member for a Wynton Marsalis concert, where he agreed to smuggle $3,000 dollars in cash back to the U.S. to relatives of a family he’d met on his first visit (“usually, it’s the other way around.”)

“I just kept saying yes to everybody,” said Gordon, explaining the attitude many early-career crew people adopt to string together steady work.

Gordon prefers working towards creative ends, as opposed to the corporate or industrial work he’s sometimes done, even if it means doing an unusual job. In the summer of 1987, fresh out of SUNY Oneonta, a New York State University, where he had a work-study job in the theater department, Gordon accepted a job with Shakespeare in the Park, a summer stage of free theater in New York City’s Central Park. Born in Long Island, Gordon arrived in the city prepared to hone the stage carpentry skillset he’d built in college. Instead, he found himself sitting in the outdoor theater five times a week guarding the production equipment—twice overnight. “It was like $270 a week, and they said, ‘there’s a baseball bat if you have any problems.’ ” Despite the potential perils of the position, the most he ever had to do was entertain a few wayward Shakespeare in the Park employees, who Gordon said would stumble into the theater after a night out in the city.

It was a co-worker at Shakespeare in the Park who invited Gordon to join the crew for “Sophisticated Ladies.” The show played in seventeen countries, as far north as Helsinki and as far south Sicily, and all the travel left an indelible mark on the young stagehand, who remembers it as a “mind blowing, eye opening,” experience.

Eventually, the miles caught up with Gordon and in 1997, after almost a decade of touring and stringing one job to the next, he returned to the city full-time. “I was like I got to stop touring, because it’s exciting and everything, but you're getting older, so it's like, I have to put roots down, get married.” That same year, he wed Nazmin Bhatia, whom he’d met a decade earlier at Shakespeare in the Park, where she was an usher. The two had been on-again-off-again since, and, once married, she moved into Gordon’s the one-bedroom apartment in Hell’s Kitchen Gordon had been renting and subletting since 1991.

Gordon began looking for more regular work with the local union I.A.T.S.E, which sent him around the corner to the Ed Sullivan theater to work on the Late Show with David Letterman. “I told the bosses, if you need anything I can be here in 5 minutes—two if I run,” said Gordon, getting his foot in the door as a reliable replacement. After nine months of replacement work, he became the house flyman, a position he still holds. In 2017 he was offered the job as House Flyman at the reopened Hudson Theater.

Between the two theaters, Gordon’s work has been steady, something Gordon, 57, is thankful for. “Working in this town—here, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Chicago and DC, to some extent, that’s where you can make a living in entertainment,” said Gordon, standing behind his desk, wearing headphones over a maroon cap as he listened for preset cues from the stage manager. “A lot of people say, ‘I can work remotely, I can live anywhere.’ I can’t do that. I’ll be here if I want to work.”

Yearning for a more rustic lifestyle, but needing to stay in New York City for work, Gordon and his wife purchased a three-story brownstone with a backyard off Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn in 2003. Since then, Gordon has gradually transformed the urban dwelling into a mock country home. He planted a Hemlock and a Cedar tree out back in 2004, and has since expanded the 1,640 square foot lot to accommodate the tomatoes, kiwis, and other produce he grows there and to install a chicken coop, which now houses five chickens—down from is apex of sixteen (“twelve is the sweet spot”), one of which is a ten-year-old Leghorn named Squash. On his roof sits six beehives, an addition Gordon made in 2016 after keeping chickens worked out nicely. Gordon gets honey from his bees, and on opening night of each production, he tries to gift his honey to an actor on the show—to help keep their voices sharp. For “Death of a Salesman,” Gordon gave a jar to the show’s co-stars, Wendell Pierce and Sharon D. Clarke.

The flow of goods between Gordon’s home and his theater goes both ways. Just off the door to Gordon’s garden sits is a red spiral staircase, wound so tight you may get dizzy walking up it, connecting the first floor to the second. He salvaged the staircase from the musical “42nd Street” as it was about to be scrapped. Gordon’s sturdy frame, draped in a blue Carhartt t-shirt and workman’s jeans, filled out the narrow mouth of the stairs, and a welcoming, short smile played across the edges of his red-tinged goatee as he recalled how he and his brother in law corkscrewed the staircase through the front door of his home during his sister’s baby shower. “These women were showing up like, ‘is this the right place for the baby shower?’ ” he said with a laugh, as his hands, thick with years of labor, mimicked the hacksawing necessary to get the staircase into the home. On a shelf to the right of the staircase, sits half of a miniature-sized model of the Brooklyn Bridge, a set-piece from Letterman’s old backdrop. That was a little easier to salvage: “my friend said just cut it in half and take half of it.”

Though he is surrounded by keepsakes from New York’s entertainment industry at home, at work, Gordon’s nestled amongst winches, wires, and screens—tokens of automation. “It’s crazy. Shows used to have like 20 guys on it,” he said. “Now, it’s like five.”

Gordon first learned automation skills in the early 2000s, well after shows began using automated fly systems. “I was way behind on this,” he said, about to describe his first automated gig, before a fuzzy voice cut across his radio.

“Jenny’s desk going out,” said the Head Carpenter.

“Jenny’s desk, going out,” Gordon replied. He hit a button, and the desk slowly slid skyward.

Jake Bolster is a freelance writer and current student at Columbia University’s School of Journalism.