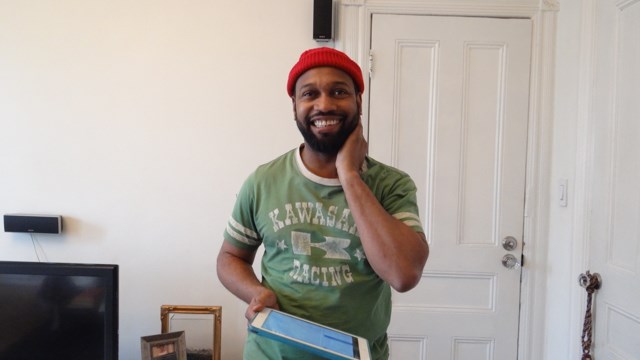

?This is where happiness truly lies,? said Bed-Stuy resident and Contemporary Fine Artist Nathaniel Mary Quinn. He was pointing at his chest.

?It?s only when you begin listening to your heart, that you will discover your genuine self... And allowing your genuine self to be is not easy; it takes courage," he added. ?But the moment I finally let go of expectation and desire, I was set free. And now, I?m happy."

Nearly 18 months ago, Quinn, 37, discovered his freedom, which then led to the birth of ?Charles.? And there's no doubt in Quinn's mind that it was only after the birth of "Charles" that his career as a visual artist took flight. Since ?Charles,? Quinn has gone from virtual obscurity, to become one of the most sought after artists in New York City, represented by one of the most reputable galleries in the world!

Photo: ced.berkeley.edu

The story of his turnaround is remarkable? one that started in 1977, when Quinn was born and when "Charles," the painting was still Charles, his brother.

Quinn grew up the youngest of five boys on the South Side of Chicago. He and his family lived in the Robert Taylor homes, the most notorious projects in the country at the time. ("We lived in what I would consider the purest form of poverty," said Quinn). The environment was violent. Both of his parents were illiterate; they could not read or write. And all of his brothers were high school dropouts.

Photo: www.viewfromtheground.com

When he was entering the ninth grade, Quinn, a bright student with a clear talent for drawing, received an academic scholarship to attend Culver Academies, a boarding school in Indiana. After only one month away at school, he received word from his dad that his mom had passed away suddenly. The following month, he returned to Chicago to spend Thanksgiving with his family. But when he arrived home, the door was ajar, and his family was gone. There was no furniture, only a few items of clothing and papers scattered across the floor.

He has not seen nor heard from his family since. That was 22 years ago. He was 15 at the time.

Quinn?s entire world was turned upside down. Yet, somehow he managed to pick up the remaining pieces, graduate from high school and go on to Wabash College where he graduated in 2000 with a double major in art and psychology.He changed his name to Nathaniel Mary Quinn, adding his mother's name, "Mary," so that she would appear on all of his degrees, since she had never obtained one herself. In 2002, he attended New York University, where he earned a master's degree in fine arts.

In 2003, he moved to Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where he continued painting while working as a teacher for at-risk, court-involved youth. As an adult, he attended therapy in an effort to reflect on and understand the anger, sadness and pain of abandonment he was feeling beginning as a teen.

?What I came to understand?which is quite beautiful?is that, as it turned out, I wasn?t abandoned by my family,? said Quinn. ?Instead, I was delivered from what would have been my destruction. Because the fact remains, my brothers were drug addicts and alcoholics. If they had been home upon my return for Thanksgiving break, there?s not much they could have done for me. But the 15-year-old me would have still accepted their embrace believing that something positive could have worked out. Now, I realize that may have not been possible.

?And for some reason, when I think about it today, I think that perhaps I was special enough? so much so? that God selected little ol' me and saved me from what could have been the end of my life,? said Quinn.

?I still feel pain about the whole thing. The volume never goes off; you still hear the noise. It still permeates throughout your soul and your heart. But I have forgiven my family and realized that in many ways, I was given a second chance to do something great with my life and do something I love. And I firmly believe that my family would have wanted the same for me."

Quinn came to terms with his circumstance, found love, married in 2010 and settled into a quiet life of teaching and painting from his tiny apartment in Bed-Stuy. Then, in May 2013, he was invited by the mother of one of his students to show for an art salon at her brownstone. He promised her five pieces. But on the day of the salon, he had only completed four. It was noon, the art salon started at 6:00pm, and he had five hours to come up with a fifth piece.

He had to think fast. He didn?t have time to make a preliminary sketch. So he did something entirely different; something he?d never done before: He let it all go.

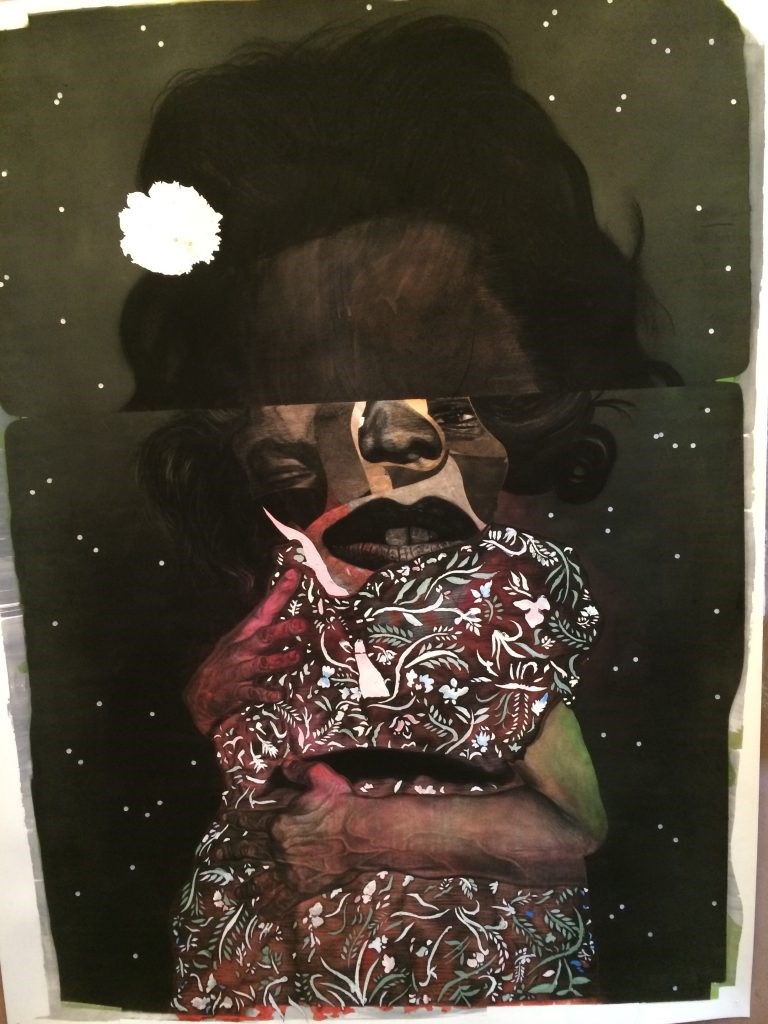

He began to paint a recent vision he had experienced, a fuzzy, disjointed memory of his past. With no clear intention, he worked entirely in the moment, hurling onto the canvas the truth of whatever expelled out of him in the moment. When he finished, he said he was ?blown away.?

?I had never made a piece like that before in my life. Never. I stood back and looked at and immediately recognized the mouth of my brother, Charles. So I named it ?Charles.??

He took his five pieces to the brownstone?one looking completely different than the four others-- and everyone immediately gravitated toward ?Charles."

?They were up in arms about it, I?ll never forget it,? said Quinn, his eyes sparkling as he recalled the moment. ?It was the first time in ten years I was truly excited about my studio practice.?

When Quinn?s friend, William Villalongo, a Yale Art Professor and well known artist with work in the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum and represented by Susan-Inglett Gallery in Chelsea saw ?Charles,? he went crazy, said Quinn. He had been mentoring Quinn for the last ten years. Yet this was the first time Quinn observed his friend and mentor react this way to his work. Soon afterward, the head of the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Art in Brooklyn saw ?Charles,? and in August 2013, agreed to display five more of Quinn's Charles-like work in their museum's windows. Villalongo soon included Quinn's work in a group exhibition that he curated at Susan-Inglett Gallery.

In January 2014, the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter wrote a positive review of Quinn's work from that show. And it?s basically been fast-forward ever since: Group exhibitions that followed include "Corpus Americus" at Driscoll Babcock Gallery in Chelsea and "Species," a one-person exhibition at Bunker 259 Gallery in Brooklyn?

The appeal of his paintings are in the heart-rousing stories, the artistic choices and also the special technique he employs to bring them each to life. He uses sketches from photographs as source material then creates charcoal drawings over gouache, an opaque watercolor-based paint on paper. There are no prints or image transfers or mechanical devices used; everything is drawn and painted by hand.

So the first thing he does is ad the color and, as an exceptional draftsman, draws on top of and around the color. Then he smudges over the paint with charcoal, followed by a meticulous erasing away of the charcoal to create shadows and reductions and other effects. Some of it looks flat, while other parts look three-dimensional. And as he?s making the work, what you see before you comes to surface entirely by means of free association.

?So everything I make is based on visions I get,? said Quinn. ?Initially, I don?t even know what the vision means. But I have a visceral response to make it, based on how I feel, as I?m constantly trying to recreate the vision that came to mind in the first place.?

?I like to give a lot of attention to the eyes and the gaze, because a it is an important point of confrontation the subject will have with the viewer,? said Quinn. ?I always to try to give the subject emotional weight, and I think I?m able to do that best through the eyes.?

And he has an interesting way of knowing when a piece is complete: ?My litmus test for knowing when a piece is done is when my mouth starts to water. If I gain a particular interest in having a nice dinner, that?s when I know the piece is done,? said Quinn.

In the past year alone, he has been visited in his Bed-Stuy studio/apartment by Beth Rudin de Woody who sits on the board at the Whitney Museum. She decided to add Quinn to a group show at the Whitney Museum, where one of his pieces fetched the second-highest bid of the evening. In April 2014, Marc Glimcher director of Pace Gallery London made a personal visit to his studio.

He was so impressed with Quinn?s work, he called him two weeks later to invite him to be represented by Pace Gallery in London. Other visitors who have dropped by his apartment and purchased his art include the vice president of the American Black Film Festival, art critic Peggy Cooper Cafritz, actors Eric Lasalle and Jesse Williams, Brooklyn Nets Deron Williams, and Derek Dudley, the manager of rap artist Common, to name a few.

Within two and half months, everything in his studio sold, and he has a fast-growing waiting list. His focus now is choosing an American art gallery (he is being courted now), while keeping up with the demand for his art by what seems like an unending list of hungry art enthusiasts.

All of this has happened for Quinn in the last year and a half, beginning with a quiet assist from his brother Charles and the moment he decided to become his genuine self; the moment he finally decided to be free.?Amazing things happen when you just let go, and make a decision to remain in the present,? said Quinn.

?I grew up in a community that was specifically designed for my destruction. Yet, I was not destroyed," said Quinn. "In fact, it was the pathway from that community that has led to my specific success. I feel like everything I have received is a direct reflection of all that I have lost. And that is just remarkable!

"It?s as though God has given it all back to me ten-fold.?