Policymakers, artists and activists from around the country gathered on Saturday in Brooklyn for a series of discussions aimed at unpacking pressing socio-political issues

The Brooklyn Museum last weekend became a virtual think tank for creativity and community empowerment, as dozens of leading policymakers, artists and activists from around the country gathered to explore how to best use local art as a platform for grassroots-led social justice.

The ambitious three-day conference kicked off last Thursday, September 19, with a keynote address by NY Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand. The next two days were filled with a series of lectures, panel discussions and performances, used to unpack pressing socio-political issues related mostly to those Americans affected by a flawed criminal justice system.

Day 1 opened with a discussion on the role of the artist in creative resistance, led by Colombian-born actress Paola Mendoza, artistic director for the Women's March in Washington D.C. at the presidential inauguration.

Although creative and productive, most of the Saturday lectures and workshops served to poke and prod at the status quo with a critical eye.

In one performance workshop designed to reinterpret stories of criminality, artist and educator Melanie Crean instructed participants to create the image of the word 'innocence' using their bodies, followed by the world 'criminal.' While most people assumed menacing positions of fist-punching or gun-wielding, one woman stood with both fists in the air, sporting a vacant expression on her face. She told Crean she was assuming the stance of a politician.

"There's something robotic about them," she said. "They dehumanize themselves because that's the only way they can make everybody else suffer."

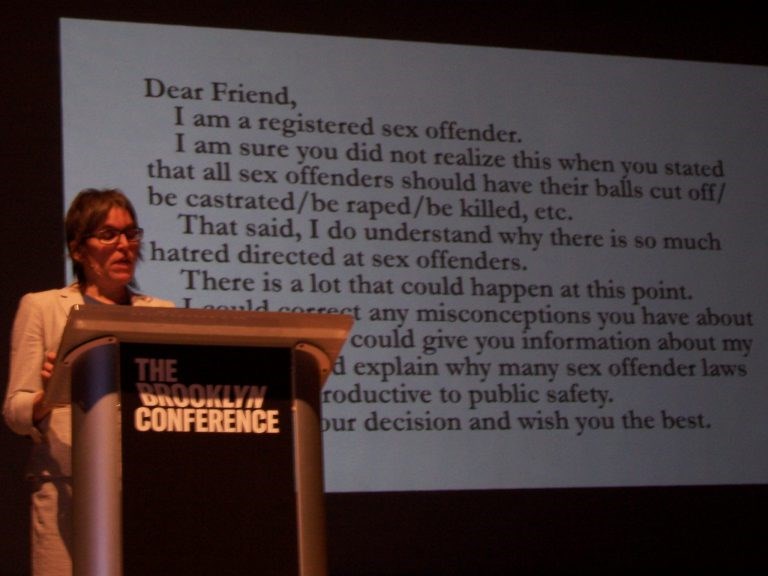

Laurie Jo Reynolds, a self-billed "legislative artist," spoke about the damaging effects of residential zoning laws for registered sex offenders. Reynolds played an instrumental role in the 2013 closure of the Supermax Tamms Correctional Center in Illinois, which placed inmates in indefinite solitary confinement. She stated that, in Illinois, sex offenders are prohibited from residing within 500 feet of a school, daycare, playground or other place where children congregate and that such restrictions result in extreme housing shortages for former inmates.

"And now because of a new law," Reynolds said, "they can be stuck in prison for life simply because they can't find housing."

Criminal justice reform continued to be the focus for much of day 2, with a panel discussion hosted by Malika Saada Saar, Google's senior counsel on civil and human rights. Saar spoke on the search engine giant's 'Love Letters' campaign, in which children sent digital love letters to their incarcerated parents.

Also on the panel was Ebony Underwood, founder and CEO of the digital platform We Got Us Now, a non-profit agency led by and for the children of incarcerated parents:

"My father has been fighting this fight ever since he was incarcerated in 1988," said Underwood, "and it's been an emotional rollercoaster, because the laws changed. But because of the lack of retroactivity in the law, he's basically stuck in legal limbo and could not utilize these laws to get out prison."

Saar said added, that in spite of these enduring setbacks resulting from a piecemeal legislative process, she saw promise in that those directly affected are now being heard: "I would say a decade ago, it was really just lawyers and policymakers in that space, especially in D.C. And what has changed so fundamentally are the voices of those who have the lived experience."

In another hands-on workshop, Lizania Cruz, an artist-in-residence at the organization Bed-Stuy Create Change, invited audience members to ponder the plight of undocumented immigrants facing an uncertain fate in today's political climate. Cruz distributed sheets of paper bearing the words "All immigrants are___. So am I," and instructed participants to fill in the blank.

The discussions also turned to race and identity and its impact on the self-esteem of children of color. Celebrated New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow talked about his daughter writing in her college application essay how proud she was to find the courage to sport her natural afro.

"Part of me wanted to applaud the bravery of it, and part of me wanted to cry," Blow said. "Because she felt that it was a revolutionary act to allow her hair to grow out of her head the way that it naturally grows out of her head."

Overall, the conference did a fine job leveraging art and creativity as a beginning discussion for grassroots mobilizing. And while some conferences of this magnitude could have easily descended into a soapbox for the airing of political, personal or professional woes, the Brooklyn Conference instead went to work.

For three days, it engaged its participants to think past the usual dialogue and generally held perceptions around racial equity and criminal justice reform and-- with a little help from some lead influencers-- develop a set of blueprints for organizing for change.